Do Grades Really Reflect Learning Anymore?

Oct 8, 2025

Kas

Do grades really reflect learning anymore? This is a thought-provoking question, and one that often comes up for those of us in education. For people outside of schooling, there’s sometimes a sense that grades are an outdated way to measure student ability. But for educators, the answer is nuanced. There’s no simple right or wrong it depends on context, assessment design, and the purpose of the grade itself.

Grades are more than numbers or letters; they’re a form of data collection. They help us measure student progress, identify strengths and areas for improvement, and to guide teaching decisions. Grades don’t always reflect the full picture; most teachers will tell you this. They rarely capture improvement, effort, or dedication in isolation (Biggs & Tang, 2011). Grades measure achievement against assessment outcomes, but they don’t encompass everything about a student’s learning, emotional growth, or effort. This is not all cases but generally speaking.

In my experience, grades are very important, but perhaps not as critical as some might perceive. A failing grade is most definitely not the end of the world or an indication of a child that is not capable, a C grade does not represent a child is average or scraping by and an A grade does not always mean a child is a genius or perfect with nothing to improve. I have seen very capable students not achieve desired grades due to the class environment, not have peers or having issues with other students. The teaching style does not suit their specific needs or they may have amotivation (lack of motivation) towards a subject area or not deem it as important, thus display a lack of effort and care. I have also seen students achieve consistently high grades but struggle when they don’t have constant guidance or feedback when it comes to tasks without structure, indicating that in a controlled environment they are able to be successful but when achieving the same outcomes in an open-ended uncontrolled environment they struggle. Grades are not always reflective of a child’s ability.

When combined with communication and discussion with students, grades provide a more complete picture of learning. On their own, they are a useful starting point but they don’t tell the whole story.

The Grading System

The modern letter grading system, commonly known by us a the A-F grading system, originated in the United States in the early 20th century, first implemented by Mount Holyoke College in 1897 to standardise assessment and provide clear measures of academic achievement (Guskey, 2015). Over time, it became widely adopted internationally and influenced grading practices around the world. In Australia, schools traditionally used percentage marks or descriptive reports but the letter grading system was adopted more broadly in secondary schools during the mid-20th century, partly influenced by international trends (MCEETYA, 2008). Today, most Australian schools use a combination of letter or standards-based grading and descriptive reporting, while senior secondary often uses scaled scores or achievement bands. Critics argue that letter grades oversimplify learning by focusing on outcomes rather than mastery or growth (Popham, 2000).

Students in early learning are graded very differently to those in junior primary, and those in primary are different to those in high school. Grading is always age appropriate in the Australian schooling system which is something I think we do very well. In my experience, assessment procedures are always adapting and improving to meet the needs of todays students.

Some examples of systems:

- Letter Grading (Alphabetic/Letter-Based Grading System): Students are assigned letters (A–F) to indicate performance, with A being excellent and F failing.

- Percentage Grading (Percentile/Numeric Grading System): Performance is expressed as a numerical percentage (0–100%), often linked to pass marks.

- Standards-Based Grading (Standards-Referenced or Standards-Based Assessment): Students are assessed on how well they meet specific learning standards or outcomes, rather than being compared to peers.

- Narrative/Descriptive Reporting (Descriptive Assessment or Narrative Reporting): Teachers provide written feedback on strengths, areas for improvement, and progress, focusing on learning growth instead of scores.

- Pass/Fail Grading (Competency-Based Grading or Binary Assessment): Students are assessed as competent/passing or not yet competent/failing, emphasising mastery over ranking.

- GPA/Weighted Grading (Cumulative Grade Point Average System): Grades are converted into points (e.g., 4.0 scale) to calculate an overall GPA summarising academic performance.

Are Grades Important?

Yes, grades are important. They provide a snapshot of how a student is performing in a particular subject. But many factors influence assessments: their design, delivery, students’ backgrounds, and even the teacher administering them. Context matters, and it varies significantly between subjects and assessment types.

Take Physical Education (PE) as an example. In my years leading assessments for both primary and high school students, I’ve seen how the type of assessment directly affects whether grades reflect true learning. Modern grading systems often separate academic achievement from effort indicators, giving a clearer picture of both performance and dedication (Thomas & May, 2010). A student may excel in effort but not reach the top academic mark, and this nuance is essential for fair assessment. In some cases, unstructured observational assessments are used, which aren’t evidence-based and often fail to provide an accurate indication of ability or meaningful data for students to improve their outcomes.

It’s also important to consider whether behaviour and effort are included in an overall grade. In most cases, these should be displayed separately either as an effort grade, a social-emotional outcome, or in whatever format your school uses but they should always be shown as distinctly different outcomes. This matters because while a student’s behaviour may influence their grade, combining the two doesn’t provide accurate data about the student’s actual ability regarding the content or a clear reflection of their effort and attitude toward the subject. Understanding their performance in each domain gives clarity and helps identify where improvements can be made. While there will often be a strong correlation and overlap between the two, it’s important to be as accurate as possible.

A country that are leaders in education (Finland) explain this clearly in the education statement:

Assessment does not focus on the pupil’s personality, temperament or other personal characteristics. Behaviour is assessed as a separate entity in a report, and it does not affect the assessment given in different subjects. (Finnish National Agency for Education [EDUFI], n.d.)

Our grading system is frequently scrutinized and I’ll be the first to admit it does need improvement and adaptation for the modern student. That said, there is a lot of innovation happening in this space. Year after year, I see small improvements being made and contemporary approaches being adopted. It’s easy to pick apart grading systems, but changing how we grade also means changing our units, lessons, pedagogical approaches, and upskilling teachers to understand these new methods. We also need to consider how these changes impact students and whether they are appropriate. It is important that these changes are made regardless of the obstacles but this takes time. So, while it may seem that progress isn’t happening fast enough, it’s important to recognise the many facets of change in educational practises. I understand it can be frustrating, but we also need to be measured in our approach and expectations and the first changes can and should happen with us in our classrooms.

Beyond the Grade

Grades represent only a portion of student learning. This is why parent-teacher interviews, ongoing communication, and rubrics are vital they provide context and deeper understanding. For some students, grades accurately reflect learning, but for others especially those at the extremes of the bell curve or with diverse learning needs grades alone may not tell the full story (Devlin, 2017).

Some of the most rewarding learning moments I’ve observed rarely appear on a grading scale: a student’s newfound confidence, improved collaboration, or growth in responding to feedback. These “wins” may not increase a percentage score but are significant indicators of learning. This is something I struggle with as a teacher, sometimes my most dedicated students don’t always achieve the grades they hope too, in these situations it is my responsibility to sit down with these children and explain thoroughly as to how the grade was decided on, the structured approach I use and what they can do next time to achieve the grade they want. Generally, these discussions go well because prior to the assessment I unpack the outcomes with all my students and they all have a clear understanding of what they need to do to achieve certain grade.

At times this is only an issue because we have a culture that is based on emphasising the importance of grades, as a teacher we need to help our students understand that these grades don’t reflect their whole ability and is not something that should shackle them and weigh them down. We need to celebrate students for effort, mindset and what they do- do well and to look at feedback as an opportunity for growth and not something negative. Learning after all is a process and not a final result.

“If assessment is not aligned with intended learning outcomes, students may achieve high grades without achieving deep learning.” Biggs & Tang (2011)

This quote underscores the challenge: grades can exist without deep learning, highlighting the limits of traditional assessment.

Viewing Grades Through the Student’s Lens

Grades shape how students see themselves. I’ve observed students who stop trying because they believe they’re “not good at it,” and others who chase grades without focusing on learning. The message students take from grades is crucial are they feedback or judgment?

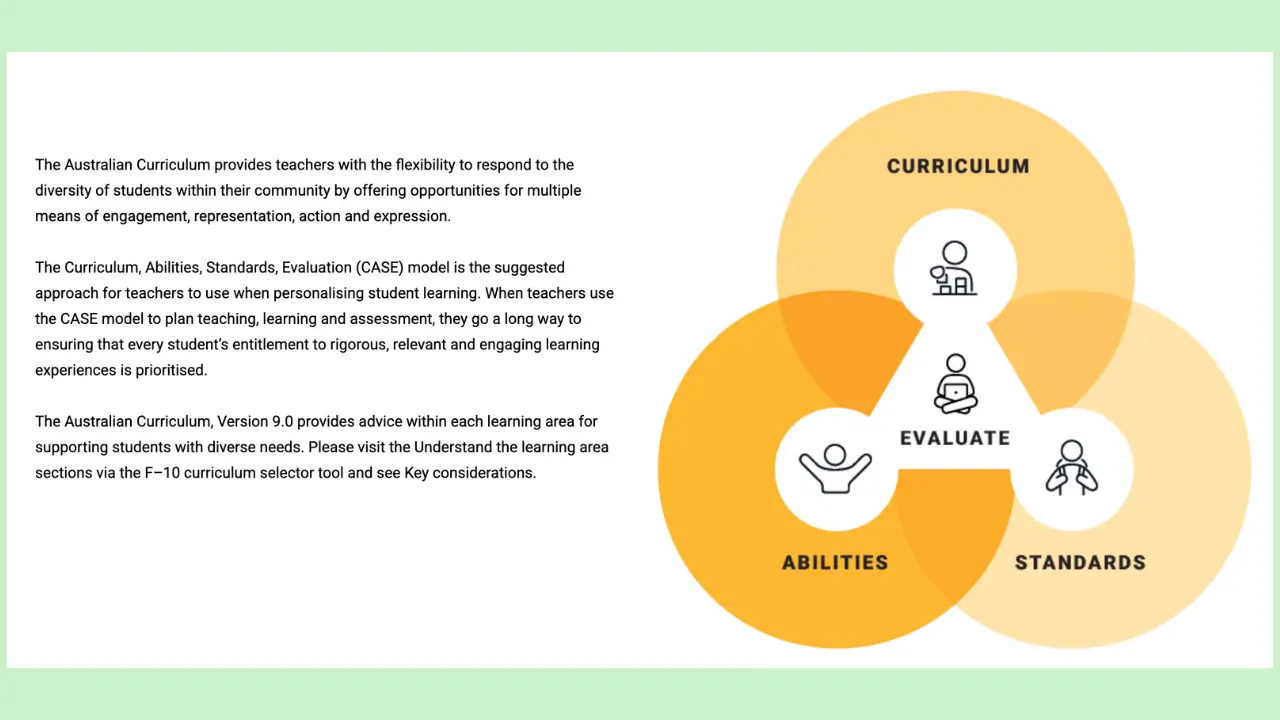

Classrooms today are full of diverse learners. (ACARA, 2024)

School students come from different social, cultural, community and family backgrounds. They also have a wide range of physical, cognitive, sensory and social-emotional abilities. Each student brings unique experiences, strengths and ideas to school.

The Australian Curriculum promotes the development of inclusive teaching and learning programs by building on students’ interests and abilities.

This diversity challenges the one-size-fits-all nature of grading. If students learn differently, should success be represented the same way for everyone?

We have to be mindful as teachers when we discuss grades, we need help our students understand that grades generally represent where a student’s learning for that topic is at not where it has ended. We also need to support students to understand that each peer comes to the class with a different set of skills, abilities, strengths and weaknesses as well as prior knowledge. Comparing grades to each other is not relevant and is not a good indicator of their ability compared to their peers. We all have natural abilities, things we adapt to quickly and things that takes us more time sometimes a topic may be easy to grasp for some whilst more challenging for others.

Grades provide us with clear markers of success against the curriculum, accountability- ensuring schools are covering the required content as per our nations curriculums standards and opportunities for communication. They inform parents, school systems and future pathways of student achievement. Yet in this process, we risk losing what matters most: growth, understanding, and reflection. Inclusive assessment design allows all students to demonstrate achievement in ways that recognise all of their strengths (Thomas & May, 2010).

Common Assessment Challenges

Many assessments are not designed with students in mind. They may lack student agency and overemphasise consistency across schools or regions. Classrooms are diverse, and assessments should reflect that. Teachers may also struggle with clarity on assessment purpose or evidence-based implementation.

Evidence-informed practice is critical. Without it, we risk systems that measure convenience rather than learning (Kyriacou, 2009; Biggs & Tang, 2011). Aligning assessments with pedagogy ensures fairness, clarity, and meaningful outcomes. Teachers play a critical role in shaping assessment. Understanding the theory behind teaching and learning is key. Kyriacou (2009) reminds us:

“Effective teaching depends upon a sound understanding of the theories of learning that underpin classroom practice.” Grading without reflection risks missing the point of education: to help students learn meaningfully.

What Effective Assessment Looks Like

outcomes are easy to understand, written in a way that anyone no matter their age can make sense of, and most importantly, they’re student-centred. Good assessments also make it clear for parents and caregivers to see what their child needs to do, while giving students a solid understanding of what they’re being assessed on and how.

An assessment shouldn’t be some secret thing that happens at the end of a unit. It should be talked about openly with students throughout the learning process ideally right from the start, but definitely not after it’s done. When possible, I think students should have a bit of say in their assessment. The ones I’ve seen work best usually have open-ended elements or at least give students some choice in how they show what they’ve learned.

The best assessments also go hand-in-hand with strong feedback models often through rubrics. These clearly outline what’s expected, linked to the learning outcomes or curriculum standards. Most use an A-E scale, breaking down what each grade looks like and what’s needed to reach it.

At the end of the day, I think it really comes down to three things: clarity, achievability, and relevance. Students need to know what’s expected, the task should be realistic but still push them to grow, and it needs to connect directly to the learning that’s taken place.

In PE, for example, strong assessments may cover three domains opposed to one:

- Practical ability: Can the student perform the skill?

- Tactical understanding: Do they know when and how to use it effectively?

- Social engagement: How do they work with others and contribute to a team?

Evidence informed: Cognitive Domain (mental skills and knowledge), the Affective Domain (emotions, values, and attitudes), and the Psychomotor Domain (physical skills and coordination). Blooms Taxonomy, 3 domains of learning.

This holistic approach gives a clearer representation of learning. A parent might question a C grade, but when unpacked, the student may excel practically but need improvement tactically or socially. Grades, when interpreted with context, provide insight into both achievement and future growth.

Final Thoughts

Do grades really reflect learning anymore? Yes, but not completely. They tell part of the story, but not the whole picture and that’s okay, I don’t think they were ever intended to. With open communication, evidence-informed practice, and thoughtful assessment design, we can ensure grades serve their purpose while capturing the broader journey of learning.

References

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Devlin, M. (2017, February 27). The typical university student is no longer 18, middle-class and on campus – we need to change thinking on “drop-outs.” The Conversation. https://doi.org/10.64628/AA.tm7trra9v

- Kyriacou, C. (2009). Effective teaching in schools: Theory and practice (3rd ed.). Nelson Thornes.

- Thomas, L., & May, H. (2010). Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: A synthesis of research. Higher Education Academy.

- Guskey, T. R. (2015). On your mark: Challenging the conventions of grading and reporting. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

- Popham, W. J. (2000). Classroom assessment: What teachers need to know(3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Ministerial Council on Education,Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA). (2008). National report on schooling in Australia 2008. Canberra: MCEETYA.

- Finnish National Agency for Education [EDUFI]. (n.d.). Assessment in single-structure education: Finland. Eurydice Finland, Ennakointi ja analyysi / Foresight and analysis. https://www.oph.fi/fi/kehittaminen/eury

Helpful Resources:

- Fundamental Movement Skills: Flash Cards + Circuit

- How to create a better work life balance?

- Why are minor games important for students to learn?

- Emotional Regulation Posters

- Assessments for P.E- Ready to go

- What are invasion games?

- First time teaching P.E? Heres where to start!